HOME THE DREAM PASSAGE ICE BOUND DELIVERANCE LOSS REFLECTION

THE PASSAGE

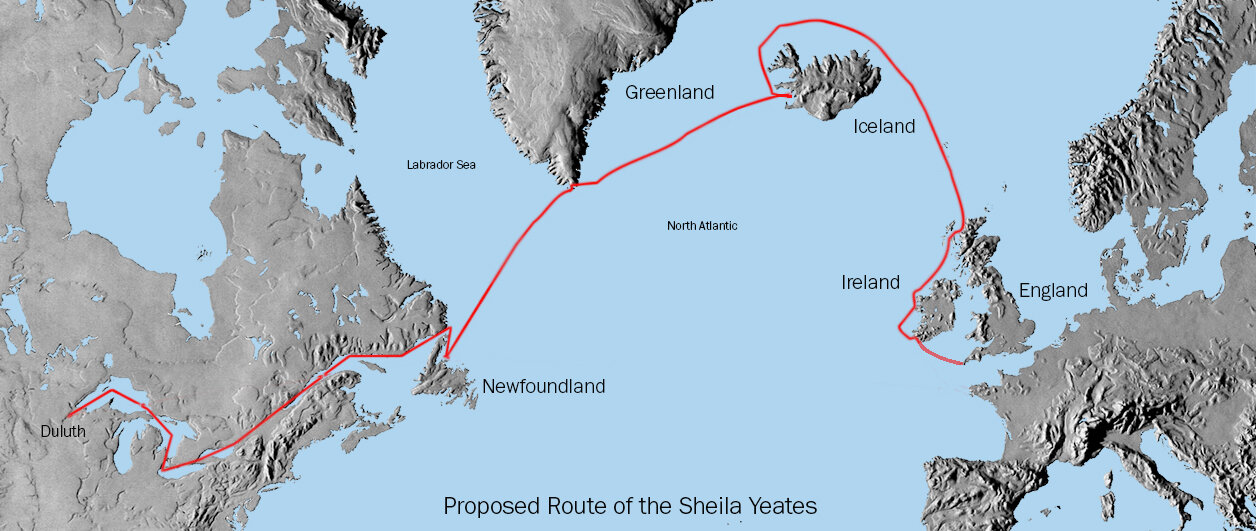

On May 14, 1989 the Sheila Yeates set sail from Duluth, Minnesota

On May 14, 1989 the Sheila Yeates set sail from Duluth, Minnesota. The log entry reads, “Chaotic departure becomes maelstrom …but departure at last.” The crew steered a course toward Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan where she would pass through the first set of locks to take her through the Great Lakes. Nearly forty different people crewed on the ship as it made its way to Newfoundland. In addition to U.S. ports, she stopped in Ontario, including Sarnia on Lake Huron, Windsor enroute to Lake Erie and Kingston on Lake Ontario.

Photo by Nate Wilson

Then she entered Quebec and the St. Lawrence River, stopping at Trois Rivieres, Quebec City and finally, Gaspe on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Various crewmembers came and went at ports of call along the way. Rick Palm came on board at Gaspe and the ship continued south to Baddeck on Cape Breton Island. Here crewmembers Mike Metzmaker and Nat Wilson came aboard, along with Geoff’s friends, Bob Crockett and his son, Rigel. Then the Sheila Yeates headed across the Cabot Strait towards Port aux Basques on the southwest corner of Newfoundland. It seemed whatever port they stopped in, Geoff knew someone who would offer a home-cooked meal and lively conversation.

“Greenland Command recommended sailing that course to 41° West Longitude to avoid ice and then to set their course east towards Iceland.”

They sailed up the scenic western coast of Newfoundland on their way to the Port of St. Anthony, their final stop before crossing to Greenland. It was ruggedly beautiful and invigorating sailing as the Sheila Yeates made good time under westerly winds. While sailing through the Strait of Belle Isle between Labrador and Newfoundland, Nat Wilson took the 2300-hour watch. “I watched the sun set, the aurora borealis light up the sky, the moon rise and the sun rise all in one watch,” Nat remembered in a recent conversation. When the ship docked in St. Anthony, a final core group of six crewmembers had assembled to help Geoff take the Sheila Yeates on her ocean crossing.

Three were from Minnesota and they had all sailed on the Sheila Yeates previously. Rick Palm and Mike Metzmaker had met Geoff Pope at midnight in southern Chile in January 1988 getting ready to sail around Cape Horn on Roger Swanson’s yacht, Cloud Nine. They became close friends of Geoff’s and sailed with him on Lake Superior. Rick would serve as first mate. Klaus Trieselmann had sailed often with Geoff on Lake Superior and was now anxious for some blue water sailing experience.

Crew Photo of the Sheila Yeates, 1989. Left to Right back row: Rob Schliz, Geoff Pope, Rick Palm, Klaus Trieselmann, Nat Wilson. Front row: David Steer, Mike Metzmaker. Crew photo by Óli Lindenskov.

In St. Anthony

David Steer and Rob Schilz joined the Sheila Yeates in St. Anthony. David was from Ontario and Rob from Nova Scotia. Still a teenager, Rob, whom the rest of the crew dubbed “the stowaway”, had the dubious distinction of being the youngest crewmember. Rob had been an admirer of the Sheila Yeates and first joined her during the Great Lakes leg of the trip. David had been a friend of Geoff’s for years and had formerly served as an officer in the British Navy. He would be ship’s navigator. Nat Wilson was a sail maker from Maine who had previously served as bosun on the 295-foot Coast Guard tall ship Eagle. Geoff had walked into his sail shop one day and they remained friends for years. Nat had made most of the sails for this voyage of the Sheila Yeates. Over the years Geoff and the Sheila Yeates had touched the lives of all six men, and now had drawn them together for this new adventure.

Bob Crockett and his son, Rigel, had hoped to be on the cruise to Greenland, as well, but plans to sail in Maine had been made months previously. Bob was a boat builder who had worked on the Sheila Yeates. Over the years, Geoff had helped Rigel sail on several historic ships encouraging a love of tall ships, which changed the course of his life. No sooner had they waved goodbye to Geoff in St. Anthony and boarded a bus home, when they decided to flip a coin whether to go back on the Sheila Yeates or stay on the bus. Three out of five flips of the coin told them to stay on the bus. So with real regret they continued home.

While at St. Anthony, the crew made repairs to the ship’s navigation system and radios. The coaxial cable for their SATNAV needed replacing. The trip along the Newfoundland Coast had registered positions miles away from their actual location. Both the VHF and single side band radios were acting up requiring the ship to be practically still in the water to get a clear transmission. The radar needed adjusting as well. Then after resupplying the ship’s larder she was ready to leave. Geoff checked the weather reports. Greenland Command noted an ice build-up near the coast but “nothing prohibitive” which translated to Geoff as a window of opportunity for the crossing to Frederiksdal and then Prinz Christian Sund Passage. The Sheila Yeates departed St. Anthony on the evening of July 6th.

Swells, North Atlantic ©2020 Nate Wilson

The crossing began in the golden glow of the low arctic summer sun, which in high latitudes barely dips below the horizon. Sea conditions were ideal and winds were slight. Daylight brought fair skies and westerly winds that drove the Sheila Yeates east towards Greenland. It was an exhilarating sail as her graceful bowsprit rose to meet the crest of each wave and then momentarily dipped in its trough as she rode the swells rhythmically, like she was designed to do. The ocean and occasional icebergs glistened in the sun and spirits ran high. At one point the Sheila Yeates was a mile from an iceberg that began to calve. The crew watched in fascination for nearly an hour, amazed at the power of these massive, mountains of ice. With light lasting well into the evening hours, the days seemed to last longer. Some nights it was 2100 hours before the crew realized they hadn’t eaten dinner.

The crossing began in the golden glow of the low arctic summer sun, which in high latitudes barely dips below the horizon. Sea conditions were ideal and winds were slight. Daylight brought fair skies and westerly winds that drove the Sheila Yeates east towards Greenland. It was an exhilarating sail as her graceful bowsprit rose to meet the crest of each wave and then momentarily dipped in its trough as she rode the swells rhythmically, like she was designed to do. The ocean and occasional icebergs glistened in the sun and spirits ran high. At one point the Sheila Yeates was a mile from an iceberg that began to calve. The crew watched in fascination for nearly an hour, amazed at the power of these massive, mountains of ice. With light lasting well into the evening hours, the days seemed to last longer. Some nights it was 2100 hours before the crew realized they hadn’t eaten dinner.

Iceberg riding the Labrador Current south between Greenland and Newfoundland. ©2020 Richard Olsenius

Geoff communicated regularly with Greenland Command as the Sheila Yeates crossed the Labrador Sea to Frederiksdal. Technically named, Island Command Greenland, it is the agency that oversees maritime sovereignty and search and rescue operations.

The Labrador Sea is an arm of the North Atlantic situated between the east coast of Labrador and the west coast of Greenland. It connects to the waters of Baffin Bay through the Davis Straight, a major highway for icebergs that have calved off the tidewater glaciers of West Greenland and are carried by the Labrador Current southward to Newfoundland. The icebergs, some as large as city blocks, make for treacherous waters.

Although summer was the best time for a crossing, strong currents from both the East and West Greenland ice fields move densely packed floes of sea ice across northern ocean waters. Along the eastern side of Greenland, the East Greenland Current flows in a southerly direction moving large quantities of polar ice along with it. The current eventually moves ice north along the western coast of Greenland, providing additional danger to shipping. Sailing near the sea ice along the coast of Greenland allows little room for error. One wrong move or miscalculation can lead to a spiral effect, where there is little chance for recovery.

Log of Sheila Yeates July 12, 1989

As the Sheila Yeates neared Frederiksdal on the southwest corner of Greenland the crew could see an ice sheet extending nearly 50 miles from shore. Geoff radioed Greenland Command. He was told the Prinz Christian Sund Passage was impassable. There would be no transiting the Passage on the way to Iceland. Greenland Command asked Geoff’s course and he told them they were sailing 100° true. Greenland Command recommended sailing that course to 41° West Longitude to avoid ice and then to set their course east towards Iceland. In the meantime, they suggested that the Sheila Yeates check in with them on an hourly basis.

Under sunny skies and calm seas, the Sheila Yeates encounters a sea ice near the south Greenland coast. Photo Rick Palm.