Journey to Khao-I-Dang

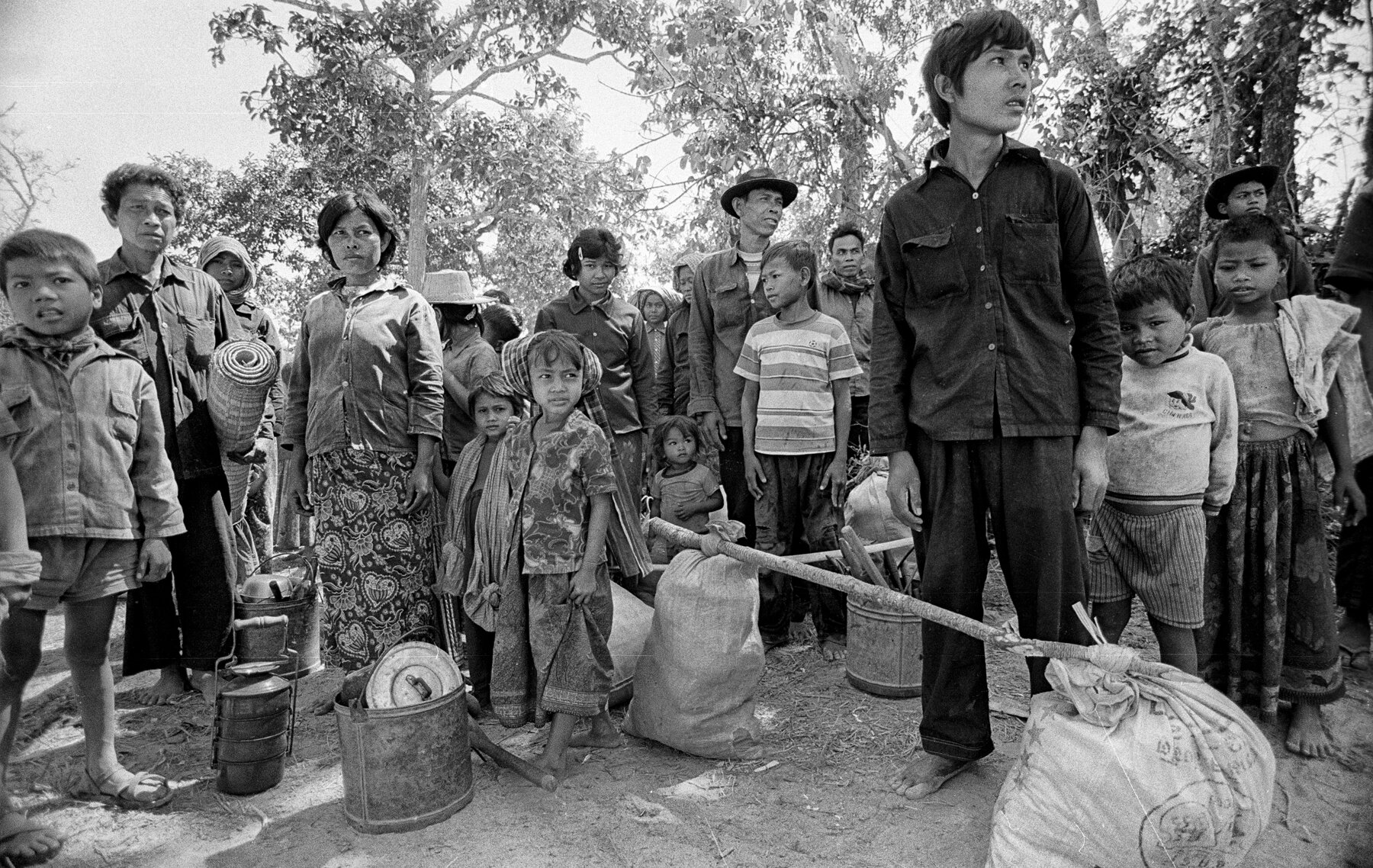

Just days before I rode a Boeing 747 8,500 miles from Minneapolis, Minnesota across the Pacific to Bangkok, Thailand, I was photographing in rural Minnesota. It was November of 1979 and I was working on a 16mm film called Autumn Passage. I remember how the thick loamy soil was covered with tall corn stalks that in a few short weeks would be harvested, fueling the agribusiness economy of the Midwest. Arriving in Bangkok and heading for the border with Cambodia, I felt a deep shock to suddenly be standing in the midst of thousands of people walking out of the thick Cambodian forest, many without shoes and carrying their entire family belongings. They had matts for sleeping, some clothes in a plastic bag, a few blackened pots and almost no food.

I can still feel this moment as if it were yesterday. I knew I had to work professionally, but there was this weight, this sense of a human tragedy being played out in front of me. No one can prepare themselves for coming face to face with the reality of genocide and an entire country pulled from its roots. I had this intense awareness of a people trying to save themselves. And what I remember most was a quiet dignity amidst all this disruption and despair. How was that possible? I developed an immediate respect for the people of Cambodia who had endured so much over the years. I hoped that with my camera, I might draw public attention to their plight.

A group patiently waiting to be processed at their arrival at Khao I-Dang.

A young man carries an elderly woman out of the jungle.

All came to the border with only what they could carry.

Crossing the fields silently

I walk a short way to the edge of the jungle where I can see streams of Cambodians crossing to the border with Thailand. It was always important to head in a westerly direction because that is where safety is and there they might find food and shelter and avoid the push of the Vietnamese solders from the east.

“Many of these refugees have lost contact with their families. Many were sole survivors of families who were dead. Many had families still in Cambodia. I talked to one 14-year-old boy that I found along the trail who had walked the entire length of the country of Cambodia. It had taken him over a year. Along the way he had lost his entire family. He crossed into Thailand and there he had collapsed and confessed that he could go no further. He was emaciated, terribly malnourished, maybe in the final stages of malnutrition; I don’t know. But the lack of social structure among these refugees was obvious. Most of the refugees had to care for themselves, and some did have the strength to do that.”

Senator Jim Sasser reporting at a Senate hearing on the Thailand Camps.

Pan Nai, 56, his wife Kid Sun, and their children Pan kieng, 23, Pan Em 8, and Pan Khev, 6 walked out of the jungle hoping to find safety and food.

Save My Family

As I walked the jungle path towards Cambodia, I saw this family coming towards me along with hundreds of other families and individuals. I made eye contact with the father and began to walk with them towards the road where the camp buses were waiting. I could not talk with them because of the language barrier, but they seemed to accept my presence. This family, like thousands of others, had left one of the over-crowed Cambodia camps called “007” run by Khmer Serei, an anti-communist guerrilla force fending off the Khmer Rouge and Communist Vietnamese forces operating in this region. The camp had nearly 200,00 people and many were not finding food or safety there since open fighting was taking place with the approaching Vietnamese army.

Pan Nai was the father, his Wife was Kid Sun and their three children were, Pan Kieng, 23, Pan Em 8, and Pan Khev 6. The Pan’s use to live along the Vietnamese border during the Vietnam War which ended in 1975. During that war the U.S. dropped concussion bombs along the border and Kid Sun had lost most of her hearing during one of those bombing runs. She later said she harbored no ill feelings towards Americans, that it was only a part of the long-fought wars in the region. But I have learned that the consequences of U.S. bombing were high. The U.S. may have dropped a tonnage of bombs on Cambodia nearly equal to all the bombs dropped by the U.S. in World War II. Estimates of Cambodian military and civilian deaths resulting from the 1969-1973 bombing range from 40,000 to more than 150,000.

Waiting after being dropped off at Khao I-Dang camp.

So I accompanied the Pan family who bravely climbed aboard one of the old buses and rode for 25 minutes to their new home at the Khao-I-Dang camp that was hurriedly being constructed. They soon stood in a newly prepared clearing and basically picked out a spot they would call home. With supplied blue tarps and bamboo poles they built their new home.

Pan Nai, 56, his wife Kid Sun.

Kid Sun and family riding the bus to their camp called Khao I-Dang, just inside the Thailand border with Cambodia.

A Home in Thailand

It appears this is where Kid Sun wants to build her temporary home.

A Place of Safety

Khao I-Dang became one of the most enduring refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border. It was established in late 1979 and administered by the Thai Interior Ministry and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).The camp population grew to roughly 160,000 before Thailand closed the camp to new arrivals.

Pan Nei shows his war damaged knee that hampers his mobility.

Kid Sun lost most of her hearing from US concussion bombs that were dropped over their home along the Vietnamese border

A New Life Begins Here

Is there any way to express the sequence of life events this family has gone through? Living along the Vietnamese border during the long US war with North Vietnam. The killing and the uncertainty of safety. To lose your hearing to a bomb blast. To endure the four years of Pol Pot with the torture and murder of so many Cambodians. To feel the onslaught of the Vietnamese driving millions of starving Cambodians westward across the country. To walk across the country carrying your belongings. To be strong for your children.

To be a family with no shoes and your clothes stuffed into a pot. And to stand in your space in a field in stifling heat and present yourself to a white photographer from somewhere unknown. To this day I do not understand the inner strength they had. Today there is a new generation of refugee’s in different areas of the world. We cannot forget nor be callous to their plight.

There is one footnote to this complex story. Lew Cope, the writer and I took the plight of this family very seriously. I could not walk away from a family who had nothing, not even shoes for their feet. So we went shopping in Bangkok for clothes and shoes and some cookware. I don’t remember the specifics of the care package, but we brought it all back for them. The difficult part to explain is that we were doing a “feel good” thing for us, something to mend the hurt of seeing so many with northing.

The sad reality was that in singling out one group with gifts, we created more of a problem for the Pan family. We could feel the resentment and jealously of the other refugees around them. Later Pan Nei asked that we not focus any attention on them. It was our mistake and I still feel badly about it to this day.