A Khmer militia patrol inside Cambodia

Young Khmer Serei soldiers man a forward trench with their AK-47 and 50 Cal. machine gun.

Crossing Into Cambodia

Ban Mak Mun camp was a stronghold for the Khmer Serei, an anti-Communist and anti-Vietnamese militia that existed just inside the Cambodian border with Thailand. This large camp or refugee city held an estimated 400,000 Cambodians who were living a fragile existence. They were being prevented from entering Thailand by the military commanders running the camp.

I walked along the dirt road towards Mak Mun with Lew Cope the writer. The stifling heat and long miles of walking made me feel like heat stroke was near. Lew insisted on wearing a pith helmet because of the oppressive sun. The pith helmet is often considered a symbol of colonial rule and it made me extremely uncomfortable. I told him I thought it would get us killed. He refused to take it off and we continued down the road with me fuming. Suddenly a squad of armed men approached us in single file. Were these Khmer Serei or Khmer Rouge? Could they be Vietnamese operating behind the lines? Such an encounter can end tragically for journalists. They walk by you and then open fire. So all we could do was smile and give a small wave. Without hesitation they broke out in laughter. I have always thought that contrary to my concern about the pith helmet getting us killed, it was Lew’s helmet that made us look harmless and humorous to the soldiers.

But unfortunately attacks on journalist have happened all too often and have only worsened since that time. Our exposure to danger was always present then, but I’m sure if I was there today, I would not walk down a jungle trail towards Cambodia unescorted.

Hundreds of unarmed men at Ban Mak Mun train in the blistering heat.

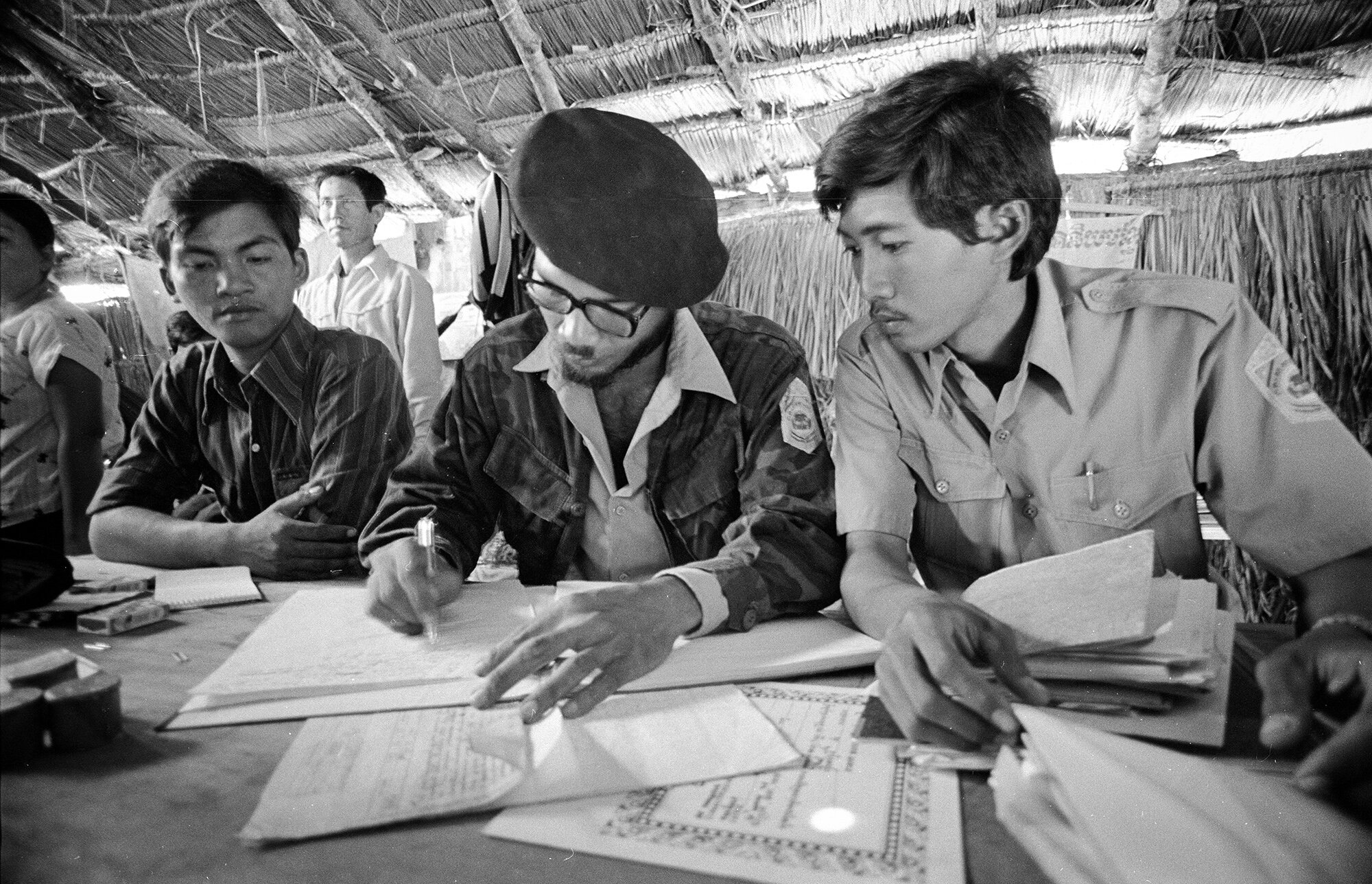

Self-named Prince Norodom Soryavong.signing a document requesting arms and supplies at Camp Ban Mak Mun.

The militia of the Khmer Serei preparing for the approaching Vietnamese army on the edge of Ben Mak Mun.

The document given to me by Prince Norodom Soryavong, asking for support and guns to use against the Vietnam and Pol Pot armies gathering along the Thailand border.

It suddenly became evident in our journey into this encampment that there was a large presence of heavily armed men and boys. They wandered around with an array of grenade launchers, AK-47’s, M-16’s and armor-piercing 50-caliber machine guns. I was shaken after a young soldier unloaded a short burst from his automatic rifle behind me into the sand. There was a big laugh from the gathered group of kids.

Now that we were inside the camp we were quickly escorted to commander Prince Norodom Soryavong sitting in a thatched hut surrounded by aids and armed guards. “We’re against the policy of mass evacuation,” said the self-appointed leader. “We don’t want our people to leave their own country. Thailand and Vietnam are collaborating to remove our people,” said another commander.

The Prince wrote out a long laundry list of military needs in french on thin parchment-like paper and handed it to me. I tried to explain I was a photographer and not an arms procurement official. I didn’t read french and I had no one to give this to of political importance. Nevertheless he gave it to me and it sits here on my desk in Arizona 40 years later. The paper is as stiff and strong as it was those many years ago but it was never delivered to anyone who could address its many requests.

My time spent in the camp was troubling because the Vietnamese had the armed Khmer Serei trapped between their troops and Thailand’s military and they were pressing in along the eastern side of the camp. I could hear automatic gun-fire in the nearby forests and at night, when I returned to Aranyaprathet to sleep, the deep sounding mortar shell blasts echoed through the night.

Suspected Khmer Rouge are tied together with towels awaiting a hearing at Ban Mak Mun.

Deadly Encounters

A young Khmer Serei soldier received a deadly head wound a few miles from the Ban Mak Mun camp, as the

Cambodians tried to hold off the the Vietnamese army pushing in from the east.

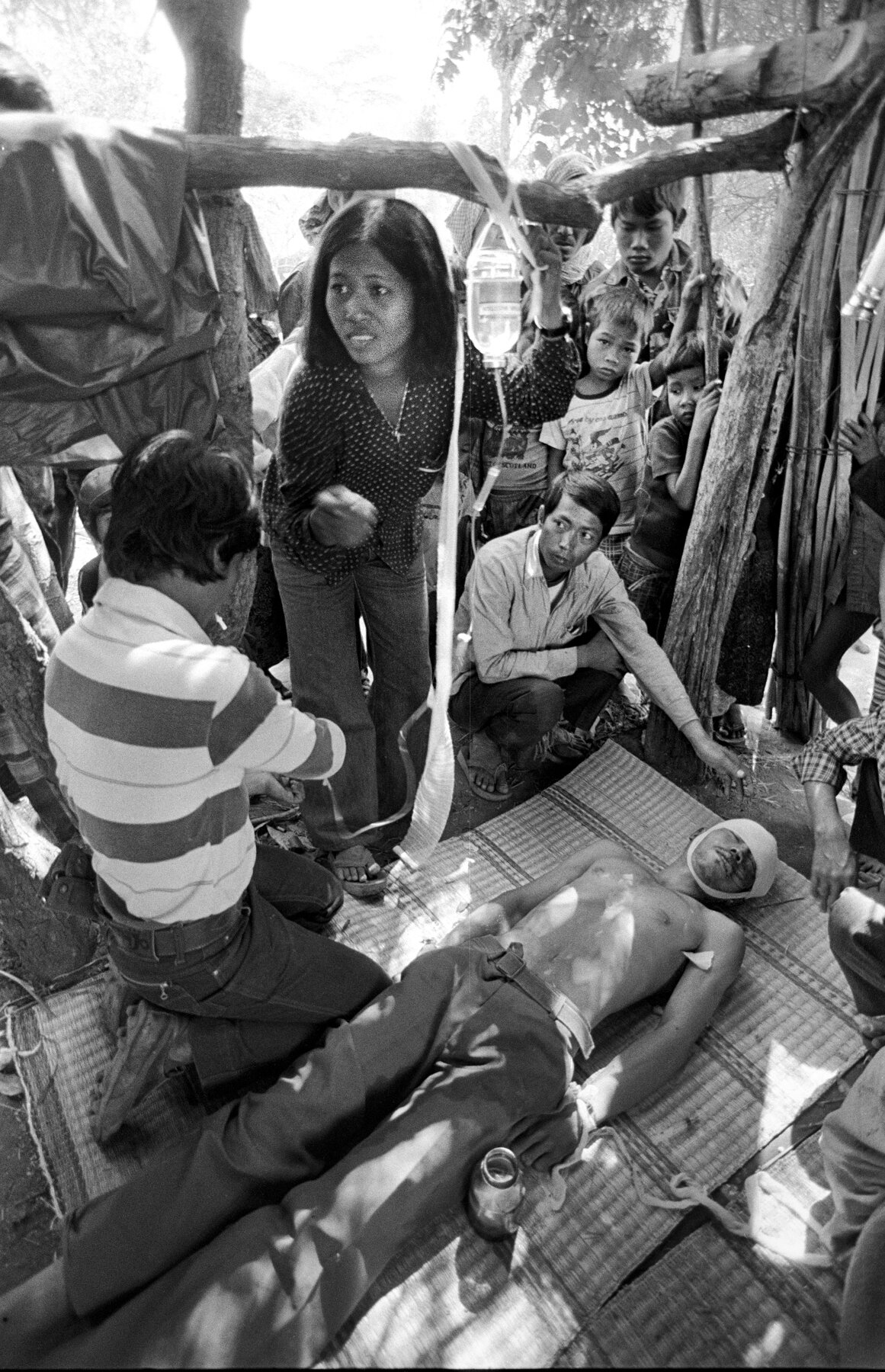

There is little medical aid in the Cambodian camps. A friend stands by giving comfort to young man shot in the chest and neck.

Much of the fighting is carried out by young boys pictured here, both with life-threatening wounds.

A wounded man brought into Khao-I-Dang medical tent.

Wounded in his hand and stomach from a land-mine, a man receives aid in the Ban Man Mun camp.

I sat in the bushes with this man as he took his last breath. There were men standing around with guns. I quietly got up and left.

Conflict and Death

“In proportion to its population, Cambodia underwent a human catastrophe unparalleled in this century. Out of a 1970 population of nearly 7,100,000, Cambodia probably lost slightly less than 4,000,000 people to war, rebellion, man-made famine, genocide, politicide, and mass murder. The vast majority, almost 3,300,000 men, women, and children (including 35,000 foreigners), were murdered within the years 1970 to 1980 by successive governments and guerrilla groups. Most of these, a likely near 2,400,000, were murdered by the communist Khmer Rouge.” R. J. Rummel was professor emeritus of political science at the University of Hawaii.

Today with Cambodia at 50 percent of its population under the age of 30, most have no memory of the “Killing Fields.”. Those who would remember it would be in their 50’s or older and that is a small part of the population. Sadly, the legacy of the genocide is fading. Like the Jewish Holocaust, the world must not forget the Cambodian tragedy that lingers like a dark cloud over Southeast Asia. These are now shadows in the sun that will remain forever.

A Khmer Serei soldier was brought in from nearby fighting with severe head wounds. A Cambodian

nurse and doctor rush to insert an IV into the unresponsive soldier who most likely succumbed to his wounds.

Khao-I-Dang medical tent where two men were brought in after stepping on a land-mine.

A Khmer Serei soldier is given a Buddhist wake in the Cambodian Ban Mak Mun camp.

Not to be forgotten

What has become of the children who have witnessed so much deprivation? Look at the children pictured here. What has become of them and their mental well-being. Forty plus years have passed and with about 16 million people in Cambodia today, it still is feeling its past. Not just the incomprehensible slaughter by the Pol Pot regime, but also a continuing civil war that lasted into the 1990’s. Studies of the 100,000 or so Cambodians who resettled in the U.S., psychologists have found a high rate of PTSD, anger, anxiety and detached feelings. Many suffer flash-backs and other mental health issues. Look at the children in this collection of photographs. Here is where these issues have taken root.